Beyond Guochao: How China’s Second Cultural Wave Is Reshaping Global Branding

- gracemu1020

- Jul 9, 2025

- 5 min read

From Labubu, vertical dramas, to century egg, Chinese cultural exports are moving fast, and brands going global must rethink how to build relevance, loyalty, and soft power.

China, never considered a country with strong soft power, is now poised to change that status quo. More and more cultural exports from China—be it content, business models, or creative concepts—are sweeping across the world and winning global audiences.

One recent sensation is Labubu. These little elves with nine distinctive teeth (the only way to tell the authentic ones from dupes) and mischievous smiles have become a global hit. This popularity has boosted the share price of its creator, Chinese toy company Pop Mart, to a record HKD 336.8 billion, making founder Wang Ning the richest person in Henan province. With its unique IP strategies, Pop Mart continues the momentum by launching more collectible characters, adored by fans and celebrities around the world.

You might not be convinced, thinking this is just another hype-driven fad bound to fade, just as I initially believed. But more and more examples are emerging that challenge that assumption. We, as Gen X and millennials raised in 1990s China, were essentially brainwashed by Western cultural products—mainly from Hollywood—and grew up worshipping the brands and services offered by Western multinationals: P&G, Unilever, Coca-Cola, Disney, McDonald’s, and the like. That’s why we now find ourselves caught off guard, even disoriented, by the rising global popularity of Chinese cultural products and content, many of which are quickly becoming global phenomena.

Now enters the mini-drama phenomenon — so addictive that it glues your eyes to your phone screen.

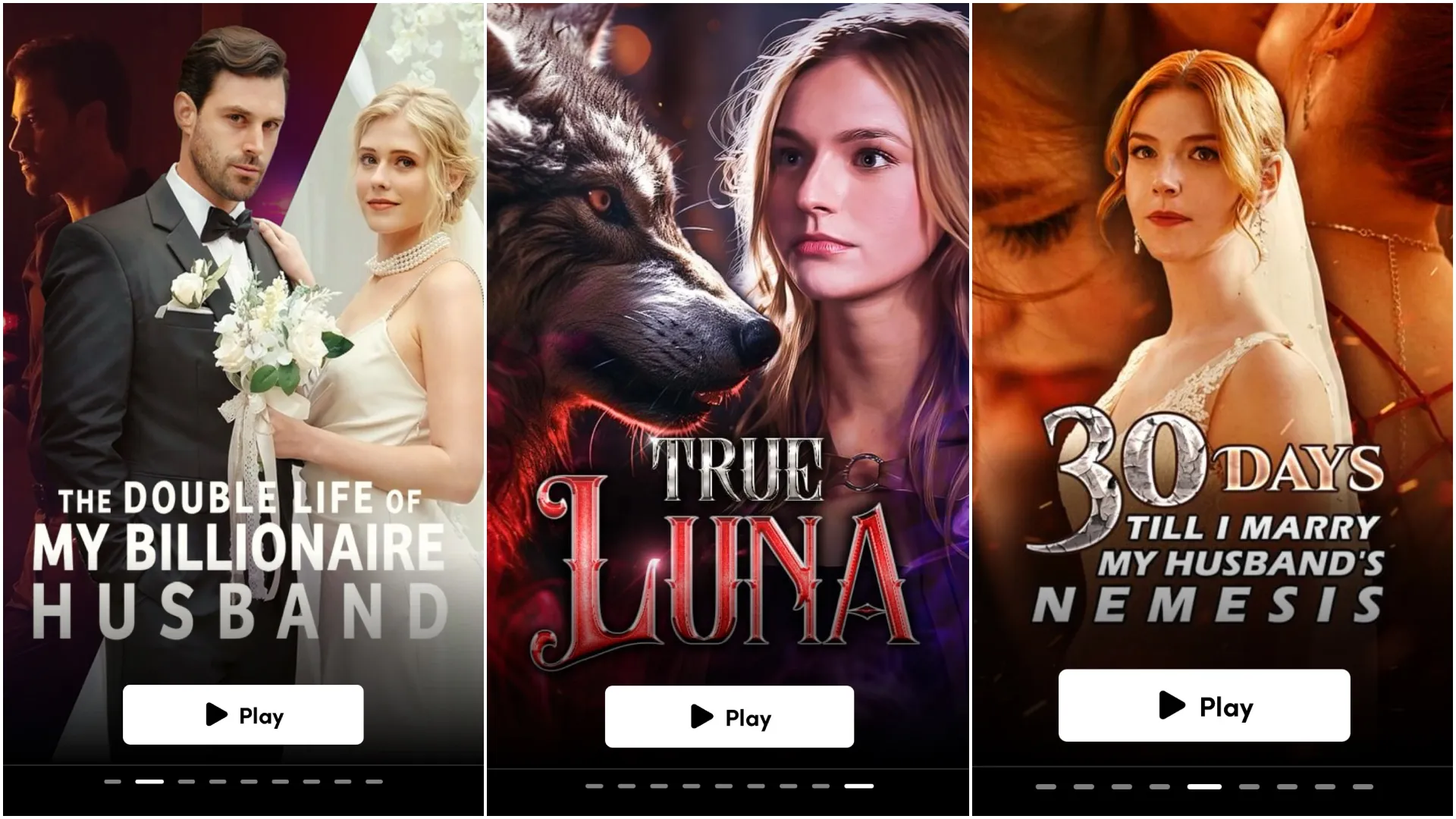

The latest wave in entertainment media—mini dramas, officially known as “vertical drama series”—was born in China around 2020, originally driven by Douyin and Kuaishou to promote product sales. Since then, it has evolved into a dominant digital format: professionally produced, made for mobile viewing, and packed with clear storylines and dramatic twists. Now gaining traction in the U.S. as an emerging market, it has surprisingly captured the hearts of “American big aunties” (美国大妈) who binge-watch these bite-sized soap operas filled with melodramatic plots (狗血剧情)—from classics like The Domineering CEO Fell for Me (霸道总裁爱上我) to Fifty Shades of Grey–style stories.

Someone joked that it’s time to redefine Hollywood with this coming wave of Chinese content exports. The trend has reversed: China, once a massive consumer of Western cultural products, is now exporting its own cultural products, content, concepts, and business models to the world.

That said, it’s still too early to call China a strong soft power nation like South Korea. Many cultural exports from China aren’t clearly labeled as “Chinese” or visibly rooted in Chinese culture. That’s quite different from brands inspired by traditional Chinese elements—products that defined the first cultural wave, known as Guochao (国潮).

What we’re seeing now—with Labubu and vertical drama series as examples—I would call “the second cultural wave.”This wave is playing out on a larger, global stage. As Yaling said in her newsletter, its identity is more ambiguous, but it has already swept the world and captivated audiences, creating cravings, obsessions, and emotional stickiness.

When you hold your Labubu bag charm in your palm and examine it closely, you won’t find any obvious Chinese markers, because it’s inspired by Nordic fairy tales and folklore. Similarly, vertical drama series, while originally rooted in narratives that resonate within Chinese culture and society, often need to be significantly reworked and adapted to fit the values and social norms of local markets. Yet they still follow the same successful formula of “feel-good drama (爽剧)” that has already proven to be a hit in China.

This is an intriguing finding, and perhaps it offers some insight into how brands can leverage cultural power to build presence, connection, and loyalty on a global scale.

First, forget national identity. It’s time to embrace universal appeal.

There’s no need to invoke national identity, especially in an era fraught with geopolitics and rising nationalism, which only serve to divide people and nations. Audiences around the world are already overwhelmed by a constant stream of distressing news: tariffs, wars, political chaos, AI anxieties, climate disasters, and more. That shared sense of fatigue and unease is a global commonality.

So what, then, is the universal appeal that most resonates across borders now?

Justice. Equality. Inclusivity.

These are the shared desires people around the world are dreaming of in this messy and uncertain era. Brands must anchor themselves in these common emotional needs when building cultural relevance. Whether it’s an elf, a CEO, or a werewolf in your story, make sure the message is clear: justice is done, and we are saved.

Second, think bigger—even if you start small.

Pop Mart’s first boutique store took inspiration from Hong Kong’s LOG-ON and Japan’s Loft. From initially selling Japan’s Sonny Angel figures, to acquiring the IP for Molly from a Hong Kong artist, to eventually becoming an IP engine collaborating with artists and creatives around the world, Pop Mart never limited its vision to China, nor confined its toy design to Chinese cultural motifs. It’s a clear example of how a local brand, guided by a global vision, can go much further.

Beyond Pop Mart, more edgy and indie local brands are following a similar path. Take Songmont, a designer bag brand, which has gone global from the very beginning, through its design philosophy and aesthetic expression. With high-quality leather and sleek design, its products recall those of top international labels. Today, Songmont has built a loyal global following, especially in Southeast Asia, after first becoming the go-to “IT bag” among Chinese women and celebrities.

And finally, don’t fear controversy. It sparks curiosity and trial.

As we all know, conversations tend to revolve around people or things that stir strong emotions, whether love or hate. That’s exactly how century eggs (also known as thousand-year-old eggs), the infamous Chinese delicacy, went viral in the U.S. after appearing on Costco shelves in December 2024.

We still don’t know whether this culturally loaded food will truly resonate with mainstream American consumers. But what it did do was spark curiosity and trial, helped along by those in the know, like The Sushi Guy, a popular food reviewer and YouTuber.

Just like the century egg, a brand that carries cultural controversy is more likely to catch attention, spark conversation, pique curiosity, and encourage trial. Some might hate it, but that doesn’t matter. What matters is that it gets noticed and talked about. In today’s attention-scarce world, conversation is currency. That’s how presence is built and awareness spreads—especially among early adopters and fans.

To conclude what we learned: the rise of Chinese cultural products is not a temporary fad but a shift in global creative dynamics. In this second cultural wave, brands—especially Chinese brands going global—should stop asking whether something is “Chinese enough” and instead focus on leveraging universal appeal to evoke cultural relevance in local markets. Soft power isn’t about flags or national pride—it’s about stories, symbols, and sensations that cross borders. That’s where brand loyalty is born.

Comments